The math of parking for a planned Forbes Ave. residential complex highlights the past costs and future promise of development in Pittsburgh

Parking space counts are decidedly the least sexy part of a new building project; site sketches and schematics provide the curious with a more immediate image of future development. But few things tell us more about who will live in a city and how they will live.

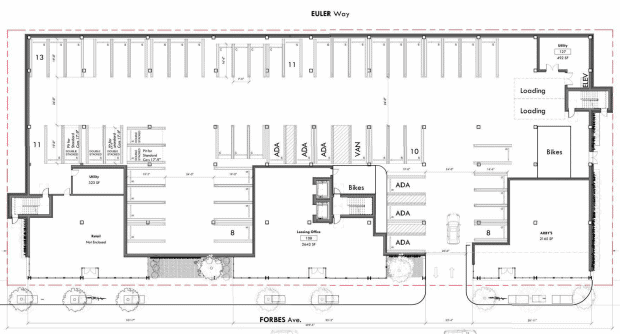

Campus Advantage, a Texas-based developer, is planning a $19 million mixed-use complex on Forbes Avenue between Halket Street and McKee Place, which will be a mix of apartments targeted at college students and street-level retail space. The proposed development covers 38,000 square feet currently occupied by vacant commercial lots, an Arby’s location, and surface parking. Design work for the new building is being managed by Desmone Architects of Lawrenceville.

The new building will contain 197 apartment units. Prior to 1958, determining the minimum off-street parking spaces required by city code for this building would have been the easiest calculation a design firm would make: 197 spaces, one for each unit as Pittsburgh’s Zoning Code. This likely would have necessitated a surface parking lot, or more expensive structured parking, that would have shrunk the amount of usable residential and commercial space, expanded car traffic in an already busy business district, and created additional car entries and exits that would decrease walkability on these blocks. At the end of the day, it probably would have made the project financially unfeasible.

Street-level view of the proposed residential complex on Forbes Avenue. Credit: Desmone Architects

This equation may as well have been carved into a stone tablet in US cities for most of the 20th century. So-called “parking minimums” set a minimum number of off-street parking spaces that developers are required to provide for newly constructed businesses or residences. Such regulations, it is thought, will satisfy the additional demand for parking created by new development that can not be met by existing on-street spaces. However, by mandating the construction of maximum parking capacity for all land uses in a given area, they have enabled the seas of surface lots that surround suburban shopping developments.

While parking minimums remain on the books in many places, they are increasingly viewed as a relic of auto-driven postwar “urban renewal.” According to critics such as Donald Shoup, a professor of urban planning at UCLA, minimums make it easier to own a car but “raise the cost of everything else,” creating additional pollution, reducing walkability, and undercutting public transit. Contrary to the claims of parking enthusiasts, the oversupply of free parking created by minimums only adds to road congestion – building more places for cars to park means more cars will need to drive.

Parking oversupply means that money, like cars, goes less far. For one, urban parking spaces are extraordinarily expensive to build. One Pittsburgh developer estimates the cost at $15,000 – $25,000 per space, a number that doesn’t include the loss of profitable space, like storefronts or apartments, that could otherwise have been built there. Broadly speaking, parking requirements complicate the quest for affordability in our cities because they cause development costs to skyrocket, limit the re-use of small lots, and raise the costs of local goods and services. Neighborhood inequity worsens.

An explainer from the City of Ottawa on the effects of parking minimums.

Recognizing their undesirable effects, a growing list of US cities have elected to curtail or eliminate these ordinances in recent years, with some even going so far as to institute parking maximums – capping the number of parking spaces that can be included in a development in order to hasten the reduction of unused parking. These measures and others such as transit-oriented development, are part of a larger set of policies that encourage neighborhoods to retain density, promote walkability, and encourage developers to build near transit hubs. Called “smart growth,” they form a cohesive vision for early 21st-century urban planning.

Add Pittsburgh to this list of progressive cities. We cut parking minimums in Downtown and relaxed them in select neighborhoods (by half in Oakland and East Liberty, and by a fourth in North Shore, North Side), a change that occurred under Mayor David L. Lawrence in 1958! 2009 revisions to zoning now allow Pittsburgh developers to forego up to 30% of these spaces in exchange for providing bike parking in the facility, a so-called “bicycle discount.”

Writing as a candidate in 2013, Mayor Peduto called minimums “one of the most regressive taxpayer-subsidized zoning requirements in use,” and advocated tying parking requirements to transit access. While they remain on the books in neighborhoods, alterations to city code like the bicycle discount and mandatory Planning reviews of local parking demand have created incentives for developers to include less parking in current designs. There are indications that City Planning and local developers are considering the design of new parking structures more carefully, and especially whether they can be converted into usable space if demand falls short of expectations — a strategy that will be put into action during upcoming renovations to the Aldi complex on Baum Boulevard.

Rendering of proposed multimodal redesign for Forbes Avenue from the Oakland 2025 Master Plan. Credit: OPDC / Pfaffmann + Associates / Studio for Spacial Practice / Fitzgerald & Halliday / 4ward Planning

While the City works toward further zoning reform, neighborhood interests also shape parking design. Jen Bee, Senior Architect at Desmone and Project Manager for the Forbes apartments, acknowledges the “complex position” of architects in the development process in Central Oakland. Schematic designs are drawn for the client and redrawn to comply with municipal code. Then there are presentations and negotiations with community organizations, often with their own vision of present problems and future development priorities.

Oakland Planning and Development Corporation (OPDC) has worked with a variety of other neighborhood organizations and stakeholders in the creation of the Oakland 2025 Master Plan, which emphasizes complete streets re-design, walkability, and the ultimate goal of “creating vibrant, diverse residential neighborhoods that are connected to high-quality multimodal transportation systems.” As OPDC Executive Director Wanda Wilson comments, “higher density developments with reduced parking requirements work in the Fifth/Forbes corridor because of the plentiful transit service and walkable urban environment.”

Under the 2025 plan, the area surrounding the Campus Advantage building is slated for multimodal street redesign, including physically separated bike lanes and pedestrian improvements in the area of Fifth and Forbes. With the impending arrival of Bus Rapid Transit lines between Downtown and Oakland, this is an area ripe with opportunity for new, transit-oriented development. There are, of course, other stakeholders to consider. The Forbes project lies adjacent to a narrow strip of residential blocks designated as a precarious “homeowner preservation” corridor in the Master Plan. Resident concerns about the impact of creeping commercialization on lower Forbes, including parking, have been registered.

The parking chair is the most visible symbol of the enduring politics of parking here, where debates flare over each new block of bike lane or townhouse construction. Residential parking is an emotional issue in cities, because many people continue to connect on-street and off-street parking. Even when the latter remains underutilized, residents wonder: will there still be space for us? But parking minimums are also important because they cut to the heart of debates over redevelopment here: our dated, car-centric infrastructure, transit deserts, and neighborhood segregation. Those are emotional issues for many others, who also wonder if there will be space for them in a future Pittsburgh.

Parking is a small stage for a big question: can we collectively manage growth — “smart”, or otherwise — in a way that serves our communities?

Don’t forget to stop by our last OpenStreetsPGH of the Summer!

Come on down and check out Open Streets for some fun on July 31st. Biking, running, walking, yoga, food, shopping, and more. Hope to see you there!