“Driving while Black” is slavery transformed

Freedom of movement is a fundamental human right. But this basic right has never been fully available to Black Americans. From slavery to the Jim Crow period to current-day “driving while Black,” African Americans moving within and between cities and states have been subject to fear tactics, violence and, at times death, at the hands of white supremacists and law enforcement. In history, the automobile often provided Black Americans increased safety and dignity compared to mass public transportation. And more currently, in a critique of rapidly implemented car-free streets during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, transportation planner Destiny Thomas asserted: “Until Black people are no longer being hunted down by vigilantes, white supremacists and rogue police, private vehicles should be accepted as a primary mode of transportation.”

And so, as we advocate for less car dependency in our communities, it is profoundly important to explore what history can teach us, because it’s not always that simple.

“Past is prologue…we study the past in order to see how it’s transformed…Because the indignities are still there.”

Craig Steven Wilder, MIT History Professor

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BLACK MOBILITY

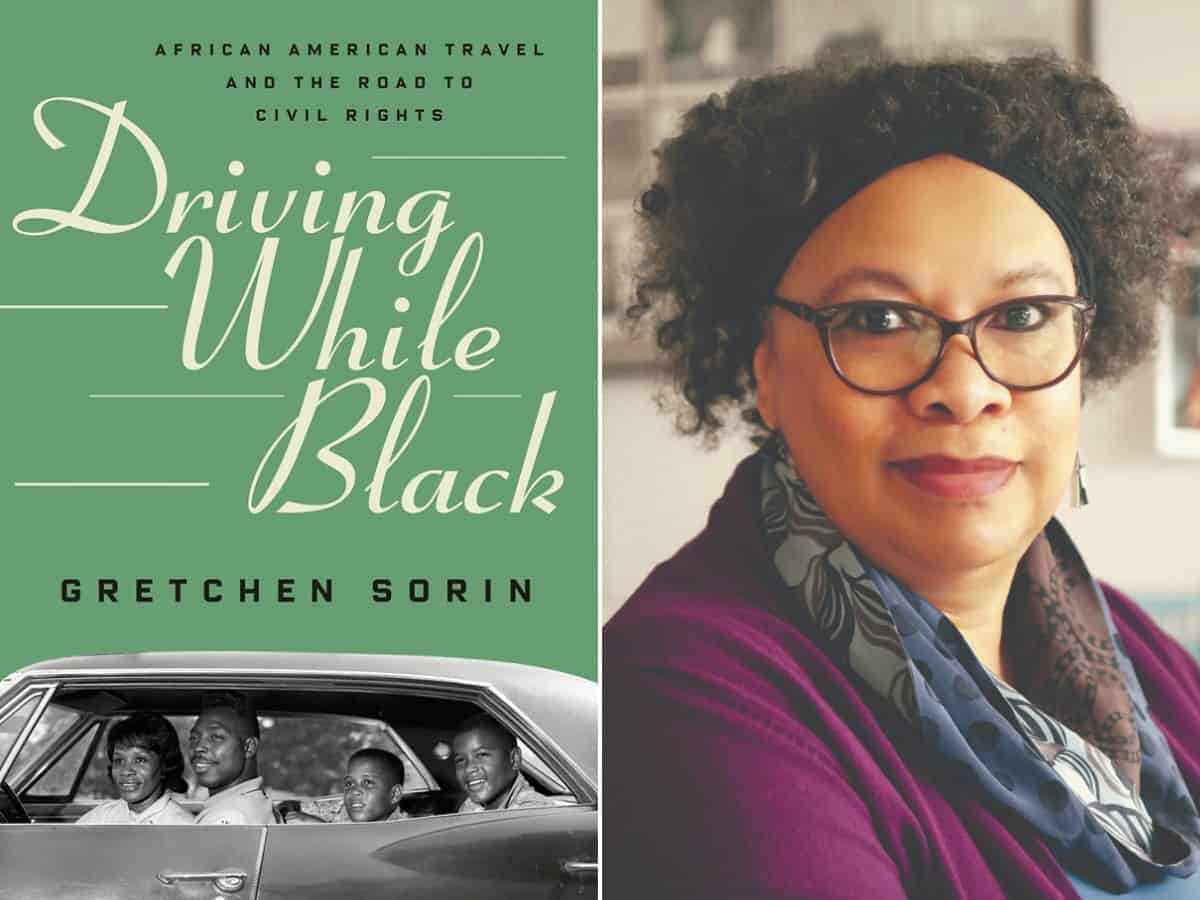

In her book Driving While Black, Gretchen Sorin draws the connection between slavery, Jim Crow laws, and the inordinate violence Black drivers face at the hands of police in cities across the US. Sorin explains that restrictions on Black mobility begin with slavery. Slavery is founded on the control of bodies; enslaved people had little to no control over where they could go or what they could do. Systems were put in place so that the movements of enslaved people could be monitored communally. Leaving enslavers’ properties required written permission. Some enslaved people who were hired out by their enslavers wore metal licenses indicating their work skills. Enslaved people who were caught trying to escape their enslavers were subject to extreme physical punishments, which at times included branding so that they would be recognized as attempted escapees.

Slave patrols, organized groups of armed white men, roamed rural Southern regions enforcing the black codes- oppressive laws that severely delimited the movements and activities permitted to Black people. Slave patrols were empowered to demand papers from any Black person they encountered, and to physically punish anyone away from their owners’ plantations without permission. Enslavers were compelled to participate in slave patrols thereby pitting “all white people against all black people.” In this way, Sorin asserts, the black codes “began the process of creating the American caste system that reinforced the notion of black people as second-class citizens (even though they were in fact citizens), and as people who needed to be controlled and contained. Many scholars now argue that slave patrols, as government-sponsored groups, became the modern enforcers of Jim Crow and the precursors of some of today’s police departments.”

During Reconstruction, travel became a space in which African Americans were reminded that a racial hierarchy was still very much intact. Formerly enslaved people were technically free but, especially in the South, still subject to many restrictions on their daily lives. Former enslavers formed groups like the Ku Klux Klan to enforce white supremacy through violence and terror. During this period railroads were on the rise for travel throughout the United States. Black people were permitted to travel only in “Colored” cars. These cars were less maintained than the whites-only cars, with smaller restrooms and no luggage racks. This segregated car was often just behind the coal car, forcing its passengers to breathe polluted air. Black passengers were not permitted in the dining car, and any food they had access to would consist of overpriced leftovers from white passengers. The same low standards were evident in train stations’ “Colored Waiting Room.” They were cramped, dirty, unheated, and had separate, inconvenient entrances.

Do you want to see safer and more accessible streets for all road users? Help us continue our work on behalf of the Pittsburgh community by becoming a member today!

At this time, travel within cities for Black citizens was also rife with indignities. Rosa Parks’ famous refusal to give up her bus seat for a white passenger set off the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56. From this, Black families were enthusiastic adopters of private vehicle ownership. Owning a car allowed an African American family to avoid the Jim Crow humiliations that defined local and interstate travel, and families could travel at will and protect themselves and their children from racial slurs and insults.

What may be less well known is the role of the automobile in making the Montgomery Bus Boycott possible. Northern supporters donated station wagons to Black churches and Black women drove people to work, school and wherever they needed to go. Black taxi drivers charged drastically reduced fares. These options along with rides offered by Black car owners provided transportation during the boycott. Due to this, the bus system was deprived of so much revenue the city eventually gave into the demands of the protestors, and their success served as a model for other cities seeking to end segregated buses.

However, the rise of the automobile in the 20th century was a double-edged sword for Black people. While it allowed personal control over the conditions of travel, during interstate trips Black travelers often could not avoid driving through hostile towns and regions. The Great Migration, when many African Americans fled South to North, saw the rise of “sundown towns.” If unfortunate enough to be caught even driving through one of more than 10,000 American towns after dark, Black travelers would be followed, harassed, or even lynched.

Even if Black car travelers were able to avoid problems posed by sundown towns, they still needed to find establishments that would provide basic services during road trips–restaurants, hotels, auto repair and gas stations. Victor Hugo Green saw the need for a guide that would direct Black motorists to such businesses. Building on the successes of earlier travel guides, he developed The Negro Motorist Green Book. The Green Book was sold at Esso gas stations, over 300 of which were Black-owned. With its nationwide lists of businesses and establishments that welcomed Black customers, this guide was considered essential for Black motorists.

PITTSBURGH: YESTERDAY…

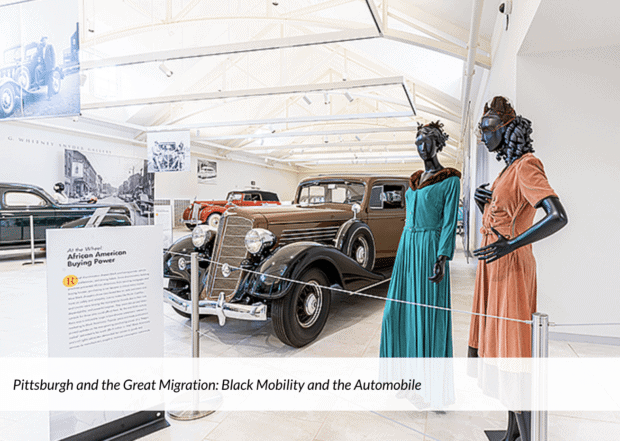

Recently, two Pittsburgh cultural institutions hosted exhibits on the history of Black American mobility. At the Frick, Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile looked at the relationship of Black Americans to the advent of car culture and private vehicle ownership. During the migration of Black Americans to the north, The Pittsburgh Courier, the local Black newspaper that also rose to national importance, advertised job openings, many of them in the steel industry. At this time, the Hill District flourished as the center of Black life in Pittsburgh. Venues hosted world class musicians and the neighborhood had its own baseball field, home to one of two Negro League teams in Pittsburgh. When Yellow Cab refused to drive to the Hill, local entrepreneurs established a cab company to serve Black residents. The country’s first EMT service started in the Hill District to serve Black residents when white-owned ambulances would not.

At the Heinz History Center, The Negro Motorist Green Book exhibition included a map of the 34 Pittsburgh sites featured in the Green Book, clustered in the Hill District. These businesses included hotels, restaurants, service stations, beauty parlors, churches, and the Centre Avenue YMCA. Despite the prominence and vitality of the Hill District, racism was rampant throughout Pittsburgh. Singer Nat King Cole and his wife sued the downtown Mayfair Hotel for refusing to rent them a room when the Hill’s hotel was full.

…AND TODAY

BikePGH aims to support communities that are looking toward a future in which all people can get to where they need to go safely. In June 2020, BikePGH issued a statement retracting our support for police enforcement as a tactic for ensuring that streets are safe for people-powered mobility. The data on traffic stops in Pittsburgh shows that encounters between people of color and law enforcement are much more likely to end in search, arrest or violence than encounters between white people and police. This disproportionate targeting of Black and Brown people does not lead to safer streets for anyone. We know that there are ways to enforce traffic laws that do not involve police. We also know that safely traveling on our streets with any mode of transportation first begins with the proper street design and infrastructure. And it also means learning from history, being aware of our individual privileges, and making sure we are always looking out for each other.

Sources / For Further Reading:

Southern Violence During Reconstruction

This Segregated Railway Car Offers a Visceral Reminder of the Jim Crow Era

How Automobiles Helped Power the Civil Rights Movement

‘Safe Streets’ Are Not Safe for Black Lives

by BikePGH Staff Contributor – Alyson Bonavoglia