Neighborhoods with low car ownership are exactly where bike infrastructure, sidewalks and transit need to be expanded

Transportation costs can be expensive and comprise a large percentage of household income. In Pittsburgh, an average household spends 17% of their income on transportation. In some neighborhoods, residents may spend over a quarter of their income just getting around. These neighborhoods tend to be lower income, but may also be burdened with poor transit service and disconnected or non-existent sidewalks and bike lanes.

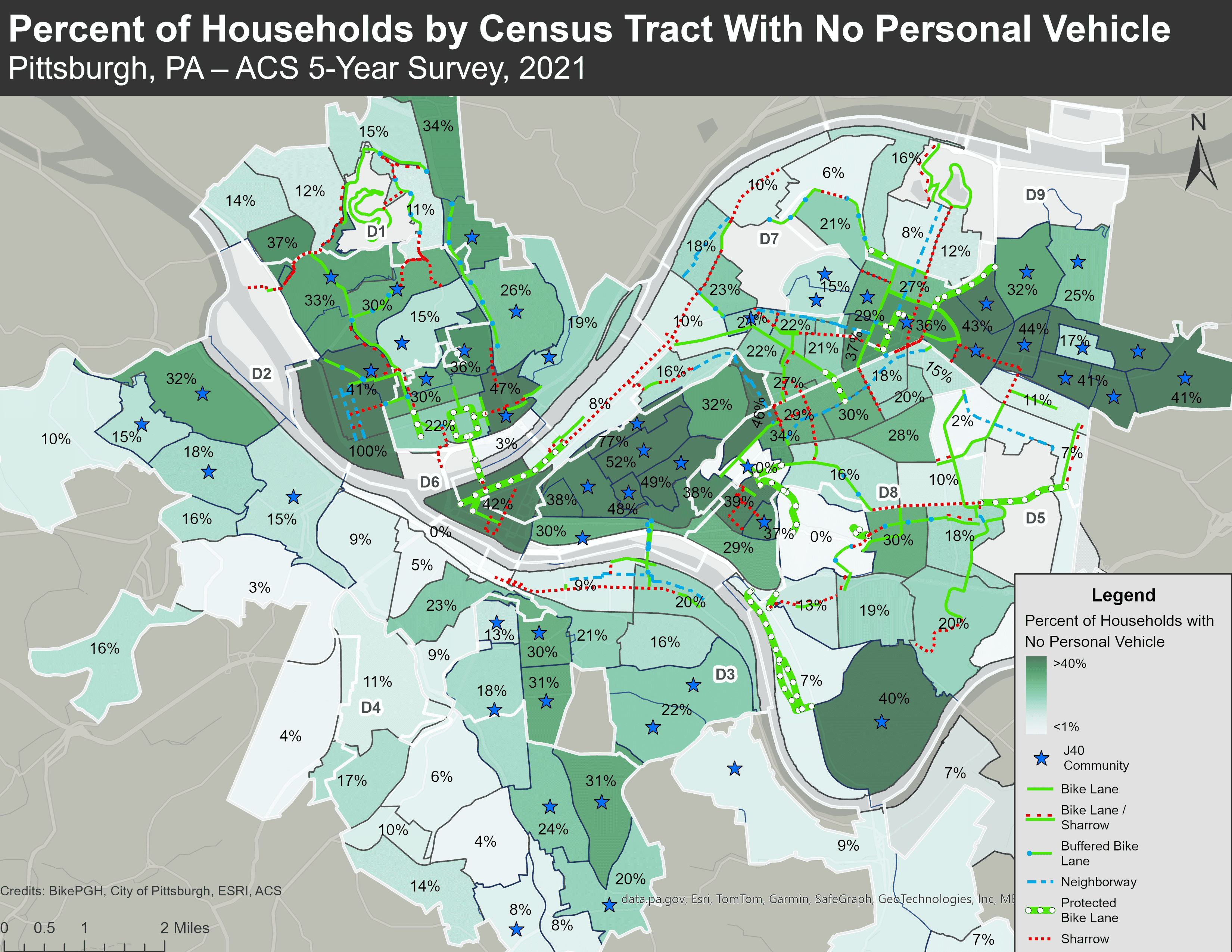

The costs associated with owning a car is one of the largest household expenses, so it’s no surprise that about a fifth of Pittsburgh households go without. When other options such as biking, walking and transit are difficult, inconvenient, or unsafe, transportation and its associated costs become a major burden that can limit opportunities that other families a neighborhood away may have.

Some areas have low car ownership rates because there is decent access to frequent transit, sidewalks, and bike lanes, saving these residents money that they can put toward other uses. Other neighborhoods have a low car ownership rate because of how expensive a car is to own, despite the lack of frequent and nearby transit, sidewalks, and bike lanes.

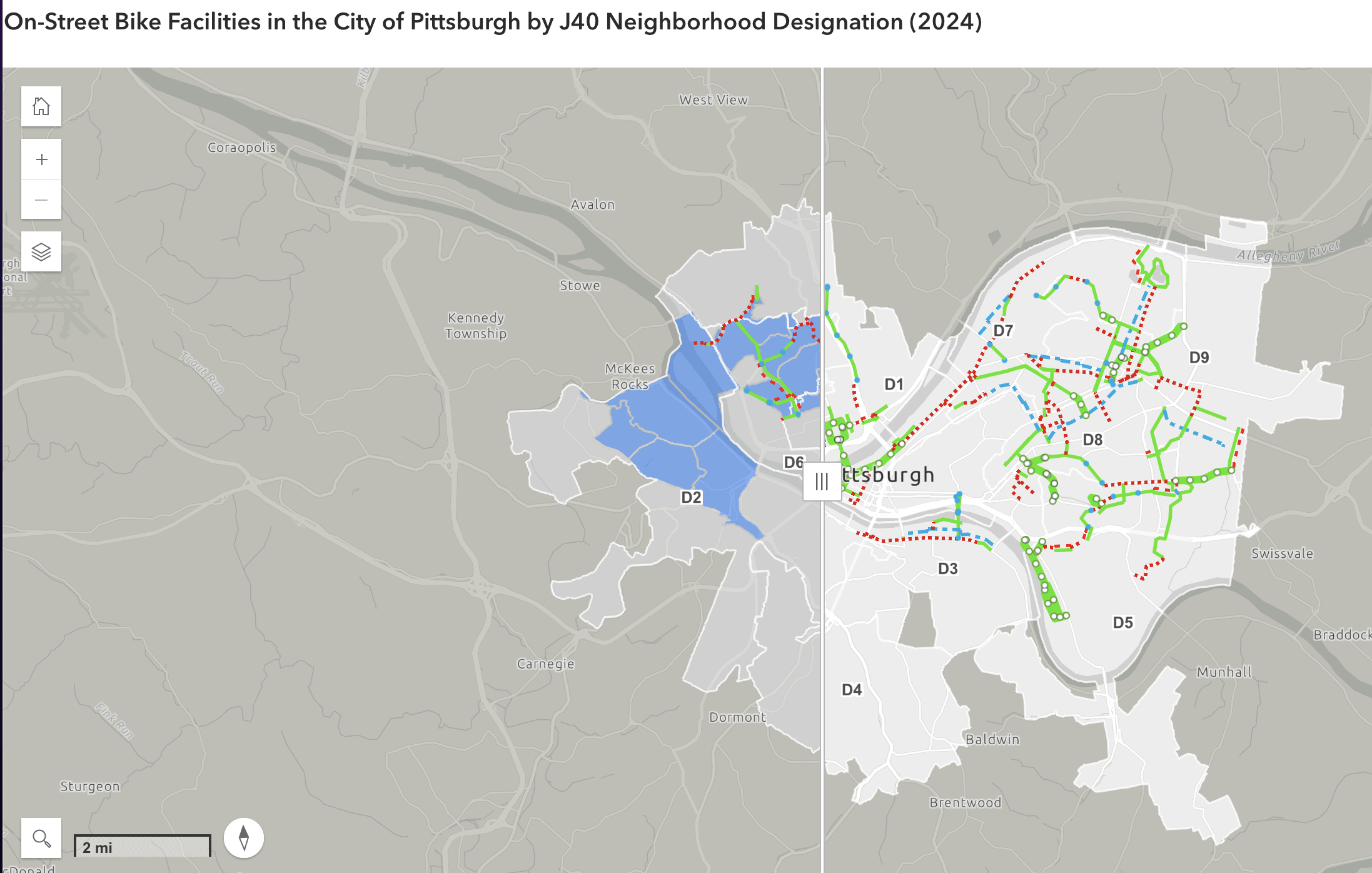

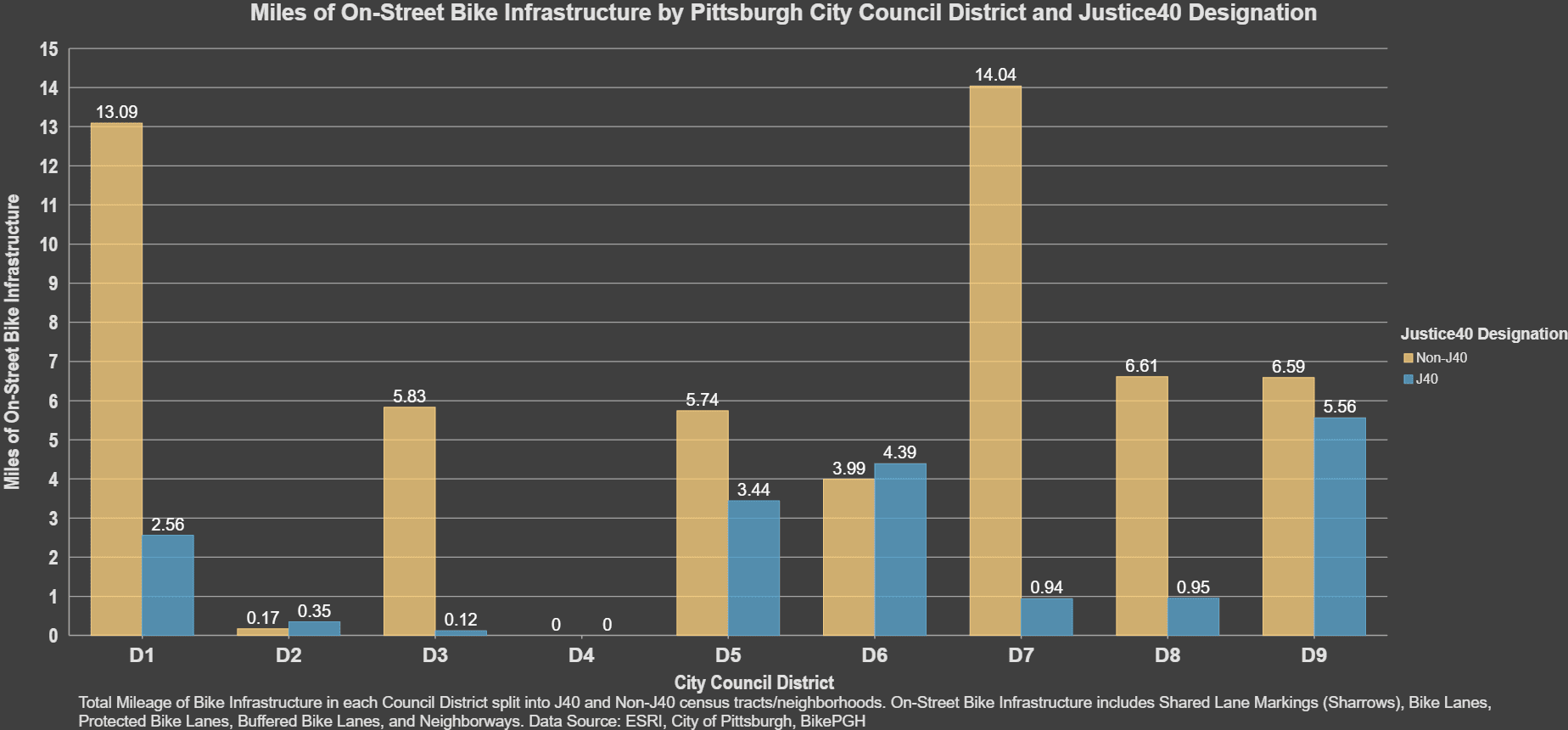

The Biden Administration has made steps to correct this disparity through their Justice40 (J40) Initiative. In short, the J40 Initiative has made it a goal that 40 percent of the overall benefits of certain Federal climate, clean energy, affordable and sustainable housing, and other investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution. The City has responded by using J40 as the lens in how they assess the level of equity in their community investments. It’s no surprise that J40 communities also have some of the lowest car-ownership rates in Pittsburgh.

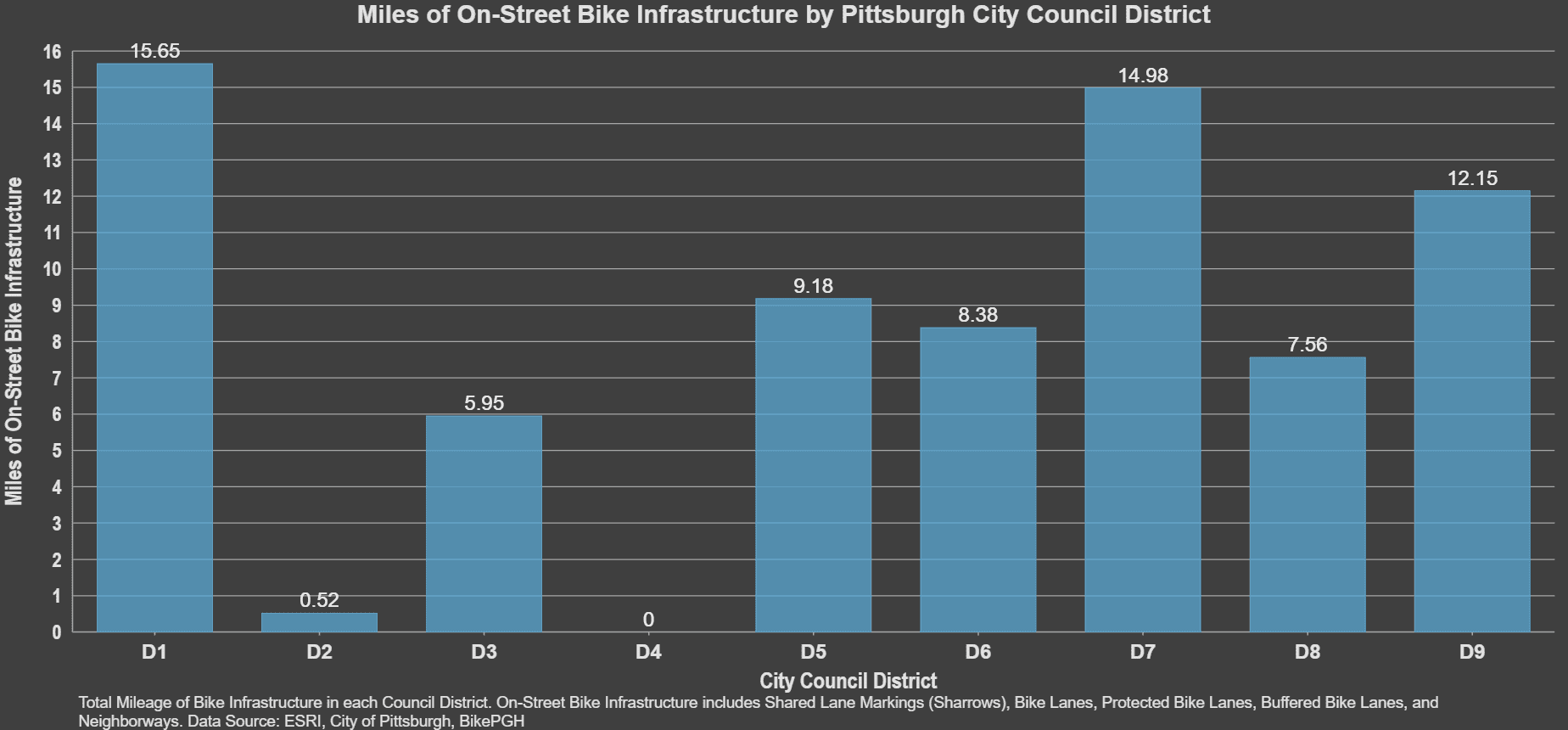

Bicycling is an affordable way to get around, bike lanes are relatively cheap to build, and could help many people access basic needs in and around their neighborhood. But bike infrastructure isn’t built equally across the city, meaning that it often isn’t in places that could use it the most. A lack of bike infrastructure makes it harder for residents to choose to get around by bike because it feels unsafe. For the purposes of this article, we are calling “bike infrastructure” any on-street markings, such as bike lanes, sharrows, and traffic-calmed neighborways as it shows a certain level of investment in the bike network. It is worth noting, however, that most council districts have at least some level of traffic calming infrastructure, which people riding bikes benefit from, but that don’t connect the bike network as outlined in the Bike(+) Plan.

The modern movement for the installation of bike lanes in Pittsburgh began in 2007 when Mayor Ravenstahl’s administration installed the the Liberty Ave bike lanes between Bloomfield and Lawrenceville. Since, the City has been steadily putting in more bike infrastructure, reaching upwards of 115 miles of on-street markings, yet not every council district has benefited equally, despite being included in the City’s 2020 Bike(+) Plan.

The reasons for this are varied and complex, but something that is certain is that every neighborhood has residents young and old who bike or want to bike for trips around their neighborhood. Some districts already have a number of people getting around by bike, so by installing bike lanes, the City is simply responding to obvious neighborhood needs. An existing base of people who ride bikes also makes it an easier sell politically speaking to make changes to the street and to parking. However, some neighborhoods may have lots of people who want to bike, but the physical and safety challenges of the hills or traffic are preventing them from doing so, and so this dynamic makes bike infrastructure seem like a more difficult sell.

Considering the benefits of providing alternatives to cars, the decision should be easy. Replacing car trips in every neighborhood will lead to more safety, less local pollution, as well as economic and health benefits for residents.

A lack of bike infrastructure is doing a disservice to residents in J40 communities

Left without choice, residents must use more time or money to access groceries, jobs, education, or healthcare, even within their own neighborhood.

It’s clear that with an increase in bike infrastructure comes an increase in bike usage by residents. While much has been done to improve the safety for those who get around without a car in most Pittsburgh council districts, some districts are still lacking a network of safe streets, leaving few alternatives for residents.

The City’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure has recognized this disparity, and have made moves to correct it, but they aren’t the only piece to the puzzle. Every district need bike infrastructure in order to fulfill the promise of the Bike(+) Plan’s goal to develop a citywide, interconnected network of safe bike infrastructure. Every resident deserves improvements to their quality of life, and that means having safe, healthy, convenient and affordable options on how to get around their neighborhood.

Many thanks to Morgan Shaw for the data assistance and GIS mapping work for this article.